Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Multivitamin on Depression

Abstruse

The role of nutrition in depression is becoming increasingly acknowledged. This umbrella review aimed to summarize comprehensively the current bear witness reporting the effects of dietary factors on the prevention and treatment of depression. PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were searched upward to June 2021 to identify relevant meta-analyses of prospective studies. Twenty-eight meta-analyses, with forty summary estimates on dietary patterns (n = 8), food and beverages (n = nineteen), and nutrients (n = 13) were eligible. The methodological quality of most meta-analyses was depression (l.0%) or very depression (25.0%). Quality of evidence was moderate for inverse associations for depression incidence with healthy nutrition [risk ratio (RR): 0.74, 95% confidential interval (CI), 0.48–0.99, I 2 = 89.eight%], fish (RR: 0.88, 95% CI, 0.79–0.97, I two= 0.0%), coffee (RR: 0.89, 95% CI, 0.84–0.94, I 2= 32.nine%), dietary zinc (RR: 0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.82, I ii= 13.9%), low-cal to moderate alcohol (<40 g/mean solar day, RR: 0.77, 95% CI, 0.74–0.83, I 2= twenty.5%), likewise as for positive clan with sugar-sweetened beverages (RR: 1.05, 95% CI, 1.01–1.09, I two= 0.0%). For low treatment, moderate-quality evidence was identified for the effects of probiotic [standardized mean deviation (SMD): −0.31, 95% CI, −0.56 to −0.07, I 2= 48.two%], omega-three polyunsaturated fatty acrid (SMD: −0.28, 95% CI, −0.47 to −0.09, I 2 = 75.0%) and acetyl-l-carnitine (SMD: −one.10, 95% CI, −1.65 to −0.56, I two = 86.0%) supplementations. Overall, the associations between dietary factors and depression had been extensively evaluated, but none of them were rated as loftier quality of evidence, suggesting further studies are probable to alter the summary estimates. Thus, more well-designed research investigating more detailed dietary factors in association with depression is warranted.

Introduction

Depression, characterized past sadness, hopelessness, lack of interest, low self-worth, and recurrent thoughts of decease, is highly prevalent amongst the general population and affects over 320 million individuals worldwide [i, 2]. It can heavily weaken sufferer's ability to cope with work and destroy their daily life skills, impose a rising burden on their families and caregivers, likewise as increase health intendance service costs [iii]. At its worst, depression can eventually lead to disability or premature death [4]. As the Globe Health Organization reported [five], depression was the main reason for inability and a major crusade for the global burden of disease. Depression has thus become an of import public health concern and investigation on the prevention and management of this disease has turned into a priority.

The pathophysiology of depression is withal vague, but existing evidence suggests that it is a complicated disease caused past the interaction of genetic, biological, and environmental factors, likely involving several mechanisms [half dozen, 7]. Although genetic and biological factors equally unmodifiable factors partly play a role in the pathology of depression, modifiable factors such as environmental factors (including lifestyle, nutrition, and social support) contribute to the onset of the disease as well [eight,9,10,11]. There has been a growing trunk of research exploring the associations between dietary factors and depression [12, thirteen]. In the last decades, many systematic reviews and meta-analyses have ended show on the associations between dietary patterns or dietary quality indices, food groups, macronutrients, and micronutrients, and the incidence of depression or the severity of depressive symptoms. These findings could be of importance for the prevention and handling of depression. Yet, the strength, precision, and quality of the evidence, and potential bias of the associations in these systematic reviews and meta-analyses still need to be clarified.

Umbrella review is a useful literature tool to provide a broad overview of published testify in systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a certain topic. They can reveal the strength of the estimates and the certainty of the conclusions, as well every bit evaluate the influence of potential bias of the associations. Recent reports summarized evidence for selected dietary factors on the prevention of depression [14,fifteen,16,17]. Strong show was constitute for a decreased incidence of depression with higher consumption of tea and dietary zinc [fourteen], and loftier adherence to Mediterranean diet and healthy diet [xv, 17], as well as an increased incidence of the disease with high adherence to a pro-inflammatory diet [xv]. Sanhueza et al. summarized convincing testify and found a decreased incidence of depression with a higher intake of olive oil, fish, folate, and omega-3 fatty acids [16]. However, none of these studies focused on any existing prove between dietary factors and the incidence of depression among the general adult population, and few of them summarized dietary gene interventions for depression treatment. Meanwhile, it remains to assess the methodological quality of the meta-analyses and quality of bear witness by validated tools. Therefore, we aimed to review comprehensively and appraise the current best evidence regarding the preventive or therapeutic furnishings of dietary factors (i.e., dietary patterns, food groups, food and beverages, macronutrients, and micronutrients) on depression amongst healthy or depressed adults.

Methods

The current umbrella review was conducted and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [xviii]. Our protocol was prospectively registered at the PROSPERO—the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (ID: CRD42021227811).

Search strategy and study pick

PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were searched from database inception until July 20, 2021, to identify meta-analyses investigating the associations between dietary exposures and depression incidence and the effects of dietary interventions on the severity of depressive symptoms. Medical subject heading (MESH) terms and keywords used for each database included "diet", "dietary patterns", "food", "food group", "nutrient and drink", "nutrient", "depression", and "meta-assay". Additional detailed search strategies were presented in Supplementary Table 1. No restrictions or filters were applied. We also screened references cited in the relevant meta-analyses by transmission. The titles, abstracts, and full texts were evaluated by two authors (YJX and LNZ), and whatever discrepancies were decided by consensus.

We included studies if the following inclusion criteria were met: systematic reviews with meta-analyses included ≥2 prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated the associations betwixt dietary factors (i.e., dietary patterns, foods and beverages, nutrients, and phytochemicals) and low incidence or the severity of depressive symptoms; conducted in full general population anile 18 years or older who behaved well mental health, were at adventure of depression (i.e., high levels of psychological mood biomarkers, sub-clinical symptomatology symptoms or vulnerability to mood disorders) or were diagnosed with low; the pooled estimate sizes [i.due east., odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio (RR), hazard ratio (HR), mean difference (Medico), or standardized mean departure (SMD)] with their 95% conviction interval (CI) were calculated.

Studies were excluded if they were only conducted among children, teenagers, and lactating/pregnant women; used a network meta-analysis method; considered bipolar disorder, secondary depression as the event; concentrated on plasma food levels or biomarkers rather than dietary intakes. A meta-analysis that pooled analysis of cohorts with individual information was not eligible for this umbrella review. If a meta-analysis included both prospective and retrospective studies, only primary studies of incident cases had been included. When more than one meta-analysis was presented in an article, we included all meta-analyses and assessed them separately post-obit inclusion criteria. For multiple meta-analyses reporting on the same dietary factor and the event, nosotros included the 1 with the largest number of chief studies. While the meta-analysis with the largest number of participants was chosen when multiple meta-analyses included the aforementioned number of studies.

Data extraction

Data were extracted initially by 1 author (YJX) using a pre-designed form and validated past another author (KZ). For each meta-analysis, the post-obit information was extracted: (1) characteristics of included publications, including first writer, journal, publication year, country of the respective writer, database searched and search period, number and type of included primary studies, as well equally quality assessment score; (ii) characteristics of the study population, including sample size, mean historic period and sex, blazon of interested exposure, intervention, comparison, and issue; (3) results of meta-analyses, including meta-analysis method, dose-response analysis, pooled estimate size with their 95% CI, heterogeneity and publication bias. For meta-analyses that comprised non only full general adults simply likewise children, teenagers, or pregnant women, we but included the effect size calculated based on general adults.

Ii researchers (XYW and SFS) independently extracted the post-obit data from primary studies included in each meta-analysis: the beginning author'southward name, yr of publication, exposure (including the dose of exposure), number of participants and cases, sex and historic period of participants, and effect size that adjusted for most confounders, along with their 95% CI, also as the adjustment factors included in the model. Any discrepancies were settled past consensus.

Methodological quality assessment and evaluation of the quality of evidence

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews version 2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist was applied to assess the methodological quality of the included meta-analyses [19], which independent vii critical domains and 9 non-disquisitional domains to capture review quality and confidence. For each item, the reply could be "yeah", "no", or "partly yes". Overall quality was rated as (1) high, no or one non-disquisitional weakness; (2) moderate, more than 1 non-critical weakness; (three) low, 1 critical flaw with or without non-disquisitional weakness; (4) and very low, more than i critical flaw with or without not-critical weakness.

The quality of evidence of included meta-analyses was evaluated using the NutriGrade [xx]. It was a numerical scoring organisation with scores ranging from 0 to 10 points, which comprised 8 items, i.e., risk of bias and study quality of the primary study, approximate precision, heterogeneity, directness, publication bias, funding bias, issue size, and dose-response association. The level of show was judged past four categories: (1) high quality, a score ≥8 points, so a reliable outcome judge may not modify in farther research; (2) moderate quality, a score of 6 to <8, indicating an effect estimate with a moderate confidence and would be changed by further investigation; (3) low quality, a score of iv to <6, where a likelihood that further studies would change the effect estimate; (4) very low quality, a score less than 4 indicated that in that location was very limited and uncertain show. All the assessments were conducted independently by 2 authors (YJX and LNZ) and whatever discrepancies were resolved by consultation to a senior reviewer (GC).

Statistical assay

We reanalyzed all the pooled estimates and their corresponding 95% CI in included meta-analyses using a random outcome model, to ensure but prospective studies were pooled and all relevant measurements, due east.yard., heterogeneity evaluation, were consistent. Every bit for primary studies that reported multiple judge sizes separately for different age, race, or sex, a stock-still effect model was applied to generate summarized effect size before the overall meta-assay. Nosotros recalculated dose-response meta-analysis if the judge for each primary report was reported separately, otherwise, nosotros extracted the adjusted summary effect size from the published meta-analyses. Pooled effect size of each dietary factor was presented in a forest plot. Moreover, we calculated I 2 as a measure of heterogeneity betwixt studies. We assessed publication bias of meta-analysis with ≥5 main studies by using the funnel plot and Egger's test. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata Version fourteen.0.

Results

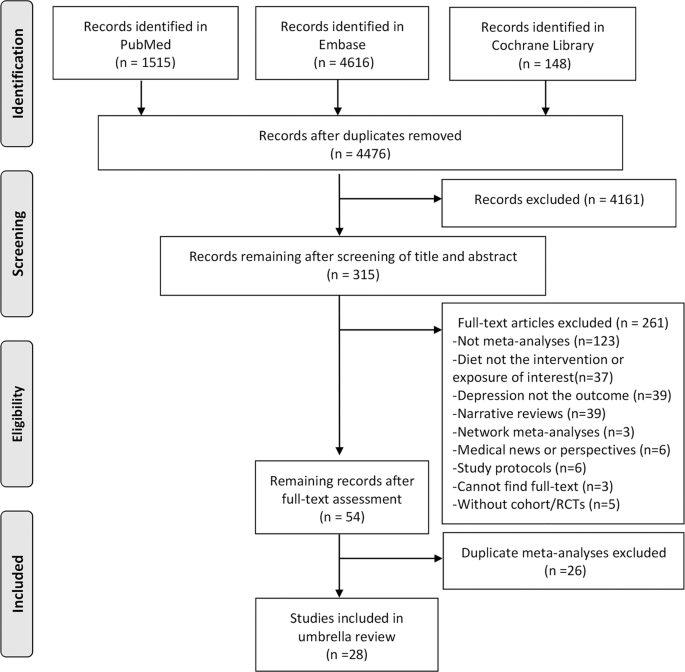

Our literature search identified 4476 publications after 1803 duplicates were removed. The period nautical chart summarizing written report pick and reasons for exclusion was presented in Fig. 1. Later on screening for 315 full-text articles, 261 manufactures were excluded according to our exclusion criteria. We identified more than 1 meta-analyses for the same exposures or interventions, and we included the recent meta-analyses with the largest number of principal studies or participants. Finally, 28 meta-analyses with 40 reanalyzed result sizes on dietary patterns or dietary quality indices (north = 8), food groups (n = 19), nutrients (n = 13), regarding preventive or therapeutic furnishings on depression, were eligible for this umbrella review.

Flow chart illustrating the literature search process in the umbrella review.

We found meta-analyses focusing on the following exposures or interventions: alternate good for you eating alphabetize (AHEI) or AHEI-2000 [21], vegetarian diet [22], dietary inflammatory index (DII) [23], Mediterranean nutrition [24], salubrious dietary pattern [25, 26], western diet [27], very low-calorie diet [28], and ultra-processed foods [29], cocoa-rich foods [30], red or processed meat [31], alcohol drink [32], saccharide-sweetened beverages (SSBs) [33], fish [34], fruits [35], vegetables [35], coffee [36], tea [37], caffeine [38], prebiotics [39], probiotics [39], and dietary zinc [twoscore], dietary magnesium [41], due north-3 PUFA [42,43,44], acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC) [45], as well equally vitamin D [46], folic acid [47], and total B vitamins [48].

Characteristics of included meta-analyses

The characteristics of included meta-analyses in this umbrella review were shown in Tabular array 1 and Supplementary Table ii. The yr of the included meta-analyses published were betwixt 2016 and 2021. The number of datasets searched ranged from 2 to eight. Well-nigh respective authors were from Mainland china (21.4%), followed past United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland (17.9%), Italy (17.ix%), Iran (14.3%), Australia (7.i%), Southward Korea (7.1%), Netherlands (3.6%), USA (three.6%), Kingdom of spain (three.six%), and Canada (3.6%). While the primary studies included in these meta-analyses were conducted in Europe (51.3%), Asia (17.9%), Due north America (15.4%), Oceania (xiv.1%), and South America (1.iii%). These meta-analyses pooled 2–26 principal studies, with the number of participants varied from 293 to 316,894. The percent of enrolled male participants ranged from 0 to 100% with the mean age ranged from 18 to 95 years. Based on all meta-analyses included observational studies, the well-nigh important confounders in the associations between dietary factors and incidence of depression included age, sexual practice, educational level, smoking, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, and other dietary factors, including total energy intake and alcohol consumption. According to the literature, the multiple logistic regression model and Cox proportional hazard regression model were used for adjusting confounders in 56% and 30% of the main studies, respectively.

The definition and criteria for low in the meta-analyses included in our umbrella review could be grouped into three categories: 8% of the studies diagnosed low by using a structured clinical interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Transmission of Mental Disorders-Four (DSM-IV), 27% diagnosed depression by self-report physician diagnosis or anti-depression medication use, others measured depressive symptoms using a diversity of questionnaires, including the Heart for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Patient Wellness Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), and the Geriatric Low Scale (GDS).

The methodological quality of included meta-analyses

The results of the methodological quality assessment were shown in Supplementary Tabular array 3. Five (17.9%), 2 (7.1%), fourteen (50.0%), and 7 (25.0%) of the retrieved meta-analyses were assessed with high, moderate, depression, and very low, respectively. Virtually of the meta-analyses had depression or very low confidence of their findings because they did not adhere to the following critical domains—(one) did non mention established review protocol earlier conduction (20 of 21, 95.2%), and (2) did non utilise a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias and account for information technology in individual studies when interpreting the results (8 of 21, 38.1%). Moreover, most meta-analyses did not report funding sources of included primary studies likewise equally perform study choice and data extraction in indistinguishable.

Associations and quality of evidence between dietary factors and the gamble of depression

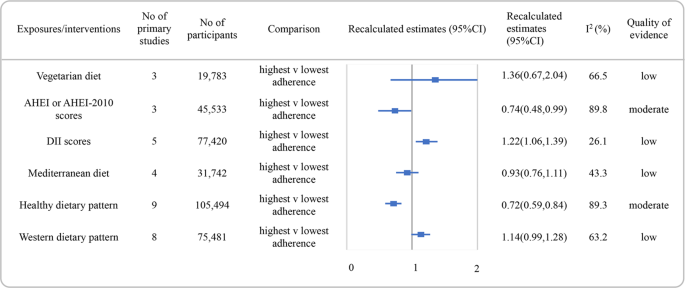

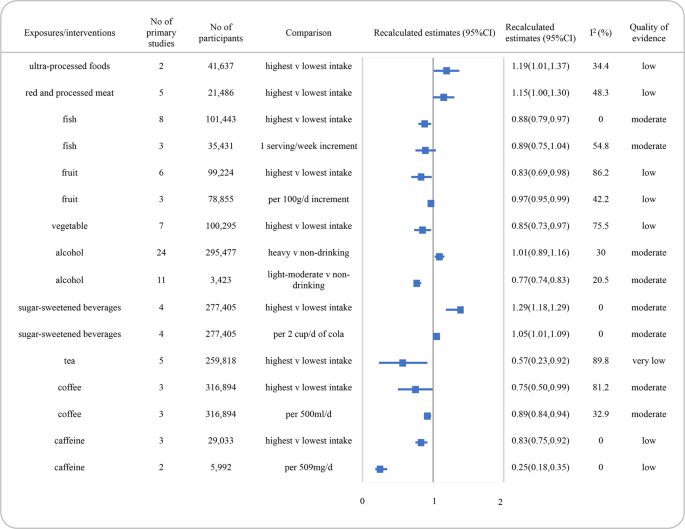

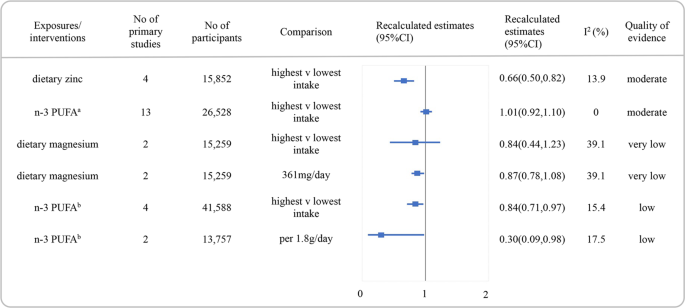

Reanalyzed gauge with 95% CI and the quality of the evidence for each association were presented in Figs. 2, 3 and iv. The particular scores of items in NutriGrade were shown in Supplementary Tabular array 4. Overall, none of the associations was graded as loftier quality of evidence. Moderate, low, and very low were evaluated for 42.ix% (due north = 12), 46.4% (northward = 13), and 10.vii% (n = 3) of the comparisons, respectively.

AHEI alternate healthy eating index, DII dietary inflammatory index, CI confidence interval.

SSBs carbohydrate-sweetened beverages, CI conviction interval.

aBased on meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, bbased on meta-analysis of cohorts. due north-3 PUFA omega-3 poly-unsaturated fat acid, CI confidence interval.

Figure 2 showed the recalculated RRs with their corresponding 95% CIs and the quality of evidence for the associations between nutrition quality indices or dietary patterns and the take chances of depression. Higher versus lower adherence to a healthy nutrition had the potential to decrease the risk of low with moderate quality of evidence (RR: 0.72, 95% CI, 0.59–0.84, I 2 = 89.iii%). An inverse clan was found between higher AHEI or AHEI-2010 scores and low incidence and also graded as moderate quality of bear witness (RR: 0.74, 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.99, I 2 = 89.8%). The associations between diet of loftier DII scores and increased depression chance were rated every bit low quality of bear witness. Additionally, no association was establish between the adherence to vegetarian diet, Mediterranean diet, or western diet and depression incidence, with depression quality of evidence.

The summary RRs for associations betwixt nutrient groups and the adventure of depression and quality of testify were presented in Fig. iii. We identified an inverse clan betwixt consumption of fish for loftier vs low comparison and depression incidence, graded with moderate quality of bear witness (RR: 0.88, 95% CI, 0.79–0.97, I ii = 0.0%). Low-quality prove was found for the associations between increased intake of red and candy meat and ultra-processed foods and the increased risk of depression. Moreover, the inverse association between intake of fruits (per 100 g increase) or vegetables and the risk of depression was graded with low also.

For beverages, the quality of evidence was moderate for a decreased risk of low with low-cal to moderate consumption of alcohol (<40 g/day, RR: 0.77, 95% CI, 0.74–0.83, I 2 = twenty.5%). While there was no significant association between heavy drinking on alcohol and low risk (>48 g/24-hour interval, RR: 1.01, 95% CI, 0.89–1.sixteen, I 2 = xxx.0%), with moderate quality of testify. Meanwhile, the changed association betwixt coffee and the risk of low (for per 500 ml/day, RR: 0.89, 95% CI, 0.84–0.94, I 2 = 32.ix%), as well as the positive clan between SSBs consumption and the risk of depression (for per 2 cups/day cola, RR: i.05, 95% CI, 1.01–1.09, I 2 = 0.0%) in dose-response meta-analysis, were graded with moderate quality of testify. An inverse association between caffeine intake and depression with low quality of show was likewise institute.

Figure 4 presented the RRs with their 95% CI and quality of evidence for the associations between nutrients and the risk of low. Moderate quality of show was discovered for an inverse association between dietary zinc and the gamble of depression (RR:0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.82, I 2 = 13.ix%). We found no association between higher consumption of n-3 PUFA and the risk of depression in a meta-analysis based on RCTs (RR:i.01, 95% CI 0.92–1.x, I two = 0.0%), rated every bit moderate quality of prove. However, an inverse association betwixt n-3 PUFA and low incidence in the meta-analysis included prospective cohorts was rated as low quality of bear witness. The quality of bear witness for the inverse association between dietary magnesium and depression was rated as very depression.

Associations and quality of evidence betwixt dietary factors and the handling of depression

Table 2 showed summary estimates with 95% CI and the quality of bear witness for each association between dietary factors and depression treatment in meta-analyses based on RCTs. We found salubrious dietary intervention significantly reduced depressive symptoms with moderate quality of evidence (Hedges's g = 0.28, 95% CI, 0.10–0.45, I ii = 89.4%). Every bit for the gut microbiota modifier, a potential treatment target, moderate quality of evidence showed that probiotics yielded modest just significant furnishings for depression (SMD = −0.31, 95%CI, −0.56 to −0.07, I 2 = 48.2%), whereas prebiotics did non differ from placebo for depressive symptoms, rated as low quality of evidence. As well, north-3 PUFA (SMD = −0.28, 95%CI, −0.47 to −0.09, I 2 = 75.0%) and ALC (SMD = −i.ten, 95%CI, −1.65 to −0.56, I 2 = 86.0%) supplementations had remission roles on depression severity compared to placebo, both graded with moderate quality of evidence. Moderate quality of evidence also concluded that no obvious effect on vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms. The quality of testify for the office of a very low-calorie diet, cocoa-rich foods, dietary zinc, total B vitamins, and unmarried folate acrid supplementation on low treatment was low to very depression.

Publication bias

Our results indicated the potential publication bias according to Egger'south exam (P < 0.1) for red and processed meat, tea consumption in meta-analyses comparing high versus low intake. The presence of publication bias was also indicated for very low-calorie diet intervention, ALC supplementation in meta-analyses comparison intervention with placebo. The funnel plots showed potential publication bias for 6 associations, including the high versus low adherence or intake meta-analyses for good for you dietary pattern, red and processed meat, fruit and tea, and the relation between treatment for depression and vitamin D and dietary zinc intervention (Supplementary Table 5)

Discussion

Main findings

The present umbrella review provided a broad overview of the influence of dietary patterns, food and beverages, and nutrients on the chance of low as well as the reduction of depressive symptoms. To our cognition, it is the first to summarize the current meta-analyses, assess the methodological quality of these publications, and evaluate the quality of bear witness for all the associations on this topic.

Xx-eight meta-analyses comprising xl summary estimates for the associations between different dietary factors and depression were identified. None of high-quality evidence was plant. Moderate quality of evidence was found for the inverse associations between good for you diet, diet of higher AHEI or AHEI-2010 scores, fish, coffee, light to moderate alcohol (<40 k/d), dietary zinc, and the chance of depression, also as for the effect of healthy nutrition intervention, probiotics, northward-3 PUFA and ALC intervention on depressive symptoms reduction. Too, there was likewise moderate quality of testify that loftier consumption of SSBs increased the risk of low. The quality of evidence of all the remaining associations between dietary factors and depression was rated equally low or very low, thus the overall summary estimates could likely to be changed in further research. In addition, the methodological quality was low or very depression for most of the published meta-analyses.

Comparison with other studies and possible explanations

Dietary factors and the take chances of low

The consistency of prove supports the protective relationship between a salubrious diet or diet with higher AHEI or AHEI-2010 scores and depression, and the positive association betwixt pro-inflammatory diet and low in our umbrella review. These findings are in agreement with published guidelines and reviews [17, 49,l,51]. A healthy diet shares a diet with a high intake of fruits and vegetables, fish, legumes, basics, and cereals, with a low intake of red and processed meat, and the contrary is true for a pro-inflammatory diet [52]. Recent investigations take suggested that depression-form chronic inflammation, oxidation stress, or defective antioxidant defenses may contribute to develop psychiatric disorders, including depression [53,54,55]. Fruits and vegetables are rich resource of fiber, minerals, phytochemicals and contain a high level of antioxidants. Increased absorption of them can reduce oxidative stress, reducing the run a risk of low [56, 57]. Our results support the inverse associations of fruits and vegetables intake with the risk of low in high versus depression consumption meta-analyses, with depression quality of evidence. A lower level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and aberration in neuroplasticity or cognitive power which are involved in the pathogenesis of depression were proven to be connected with a high level of saturated fats in carmine and candy meat [3, 58]. Our overview also plant a harmful relationship of the risk of low with a higher intake of carmine and candy meat. Likewise, fish and basics comprise high levels of n-3 PUFA, which has the potential to forestall low through anti-inflammatory effect, neuro-endocrine modulation, and neurotransmitter activation [59,60,61]. The inverse association between fish or northward-3 PUFA and depression incidence, with moderate or low quality of prove, respectively, was also found in this umbrella review. Furthermore, the meta-analysis based on RCTs showed inconsistent conclusions on the effect of n-three PUFA on low incidence, partly due to their short-term trials (no more than 12 months), limited dosages or variations on north-3 PUFA sources, and so on. Thus, further research in this area to investigate the direction of this association is needed.

At that place was moderate-quality evidence for negative effect of SSBs on the chance of low that was identified in our umbrella review. The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) project from 1999 through 2016 among 15,546 Castilian academy graduates with 769 depression cases found that the highest intake of added carbohydrate consumption was associated with increased depression take chances [62]. Further study from the Whitehall II written report too found that sugar from food and beverages was related to college depression incidence, prevalence, and recurrence of mood disorders, including low [63]. Evidence from beast studies has turned out that a diet rich in sugar during peri-adolescence increases depressive-like behavior in their adulthood via activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and inducing tiptop in glucocorticoids [64]. As the largest consumer of SSBs, overconsumption of added sugar during boyhood also is likely to promote long-term dysregulation of the stress response [65]. In improver, SSBs are partly responsible for obesity and may predict impaired glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance leading to type 2 diabetes [66]. And a bi-directional human relationship betwixt obesity or type Ii diabetes and depression has been reported in prospective enquiry [67, 68].

Booze has been reported to associate with depression. Previous cantankerous-sectional studies ended that problem drinkers were more vulnerable to develop low [69, seventy]. But individuals with low were more than likely to take alcohol misuse to relieve their distress, which might lead to an overestimation of the effect of alcohol on the risk of depression. In our umbrella review, we included the meta-analysis of longitudinal studies to avoid bias and found that more than 48 g alcohol intake per day did non increment depression incidence, with moderate quality of prove. Moderate quality of evidence was as well identified the inverse association between less than xl g alcohol intake per day and the risk of depression. This is consequent with a previous genome-wide analysis, which reported the chancy consequences related to alcohol were more genetically associated with depression than booze intake itself [71].

A high intake of coffee was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of depression in our study. Recent evidence suggested that coffee had several potential effects on health, including the prevention of cardiovascular run a risk factors, metabolic diseases, cancer, and depression [72,73,74,75,76]. Nevertheless, the machinery behind the preventive result on low are unknown. There are some hypothetical biological explanations. As an excellent source of caffeine, java has the potential to stimulate the central nervous arrangement and enhance dopaminergic neurotransmission [77]. Our findings likewise back up this hypothesis to a certain extent, because caffeine has been shown to reduce the risk of depression with low quality of prove. Across caffeine, several compounds in coffee may play a role in preventing depression. For instance, chlorogenic acid, catechol, trigonelline, and N-methylpyridinium contained in coffee have been proven to counteract the depressed condition via increasing calcium signaling and dopamine release [78]. Nevertheless, tea that is rich in caffeine and phytochemicals is not associated with the chance of depression, more research is needed to explore this field in depth.

Dietary factors as treatments for depression

Guidelines suggest a combination of psychological and pharmacological therapies to treat depression [79, 80]. Currently, upward to 60% of the patients with low feel some degree of nonresponse to pharmacological treatment, because of delayed onset of effect past targeting neurotransmitter activeness [81]. Meanwhile, incomplete compliance with antidepressants is also frequent, mostly owing to their agin side-effect [82, 83]. Consequently, research exploring novel treatment approaches is growing, and nutritional psychiatry becomes a newly emerging field aiming at nutritional prevention and treatment strategies for psychosomatic diseases similar depression [84]. In this umbrella review, we identified the therapeutic effect of n-three PUFA, ALC, and probiotic supplementations on depressive symptoms graded with moderate quality of evidence, equally well as for dietary zinc on low treatment rated every bit depression quality of evidence.

Long-chain north-3 PUFA, particularly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) [85], has been considered to be used every bit an adjuvant treatment for major depression thanks to their anti-inflammatory activity and maintenance of membrane integrity and fluidity [86, 87]. All the same, we could non draw a conclusion on the optimal dosage of DHA or EPA contributing to improvements of depression, limited by heterogeneity between principal studies in this study. A recent pairwise and network meta-assay found that a high dose of n-3 PUFA (<2000 mg/d) might be superior to a low dose of n-3 PUFA in the early on stage of major depressive disorder [88]. Information technology was establish that EPA combined with DHA therapy had significantly reduced the severity of depressive symptoms compared to the DHA monotherapy [89]. Furthermore, proper proportion on DHA with EPA is another key consideration in current studies. Song et al. found that 2:1 or 3:1 of EPA to DHA would be the most effective for depression [xc]. Similarly in the other 2 meta-analyses, the effective ratio of EPA in treating low was EPA ≥ 80 or ≥60%, respectively [91, 92]. These proportions may lie in the fact that EPA has a improve antidepressant outcome. In contrast to DHA, EPA tin rapidly enter the encephalon and quickly act as an effector [85]. EPA and DHA can deed equally natural ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and inhibit the neuronal para-inflammatory pour in the pathophysiological process of depression [93]. DHA binding depends on concentration, while a low concentration of EPA could bind with very high affinity to all PPARs [94]. Even so, we could not determine the efficacy occurs because of EPA alone or because of an interaction with DHA supplementation, and the optimal proportion or dosage of both DHA and EPA supplementation in improving depressive symptoms. Therefore, hereafter studies should deeply explore the anti-depression effect of DHA and EPA from the aspects such equally different populations and appropriate dosage.

Recently, circuitous bi-directional communication betwixt the gut and the brain has been identified to play an of import role in the pathology of depression [95, 96]. Probiotics, as gut microbiota modifiers, concord item appeal partly for depression treatment. Marcos et al conducted the first study to explore the relief efficacy of probiotics on depressive symptoms amongst healthy students in 2004 [97]. During the concluding decades, a growing number of studies take confirmed the anti-low properties of probiotics in healthy populations [98, 99]. Yet in that location is limited evidence from clinical trials of clinical depressed populations. Our findings indicated a benign association betwixt probiotics supplementation and the handling of low amid depressed patients, merely with a loftier chance of methodology bias and moderate quality of evidence. The number of RCTs in this overview was limited, and there was a large gap among the chief trials on the characteristic of participants, type of intervention, intervention duration, and combination of probiotics strains, which reduced the capacity to draw a clinically meaningful conclusion. At that place is an urgent need to determine the verbal effect of this novel handling approach, and to investigate potential underlying mechanisms. Further well-designed studies should: (ane) consider differences in microbiome composition across the lifespan; (ii) explore specific probiotics combination according to all ages of patients with depression; (3) have inter-individual variation into business relationship.

Carnitine, widely known for its office on peripheral lipid metabolism, has been reported to take role in brain lipids synthesis and improve neurofunction via increasing antioxidant activeness and enhancing cholinergic neurotransmission [100]. Of particular interest, ALC has been recognized as an effective treatment for geriatric depression, which is associated with the normalization of phosphomonoester levels in the prefrontal region [101, 102]. A recent meta-analysis found that ALC was effective and tolerable for general adults with low [103]. Our findings confirmed the therapeutic effect of ALC amid general depressed adults. Future studies with a larger sample size could be of importance to examine whether ALC is applicable in the general population without inacceptable adverse furnishings.

Micronutrients take been deemed to exist the most prominent and valid substitutes for a monoamine-based antidepressant. Several studies have concluded that zinc impecuniousness could induce depressive-like beliefs, while zinc supplementation could opposite the situation effectively [104, 105]. Similarly, findings from this umbrella review showed mood-improving properties of zinc supplementation among patients with depression, evaluated with low quality of evidence. Even so, we still need to be cautious with the conclusion. Commencement, it was difficult to distinguish the true effect of zinc supplementation on the severity of depression on business relationship of variations in criteria of depression grades in primary studies. Additionally, whether zinc supplementation has sustainable effects remains unknown, which provides a feasible avenue for further research.

Strengths and limitations

Our umbrella review had several strengths. It was the showtime broad overview of the meta-analyses on the association of whatsoever dietary factors and the prevention and treatment of depression. We had taken measures to minimize bias in the umbrella review, e.g., recalculating all meta-analyses using a random effect method, conducting the review process by two authors independently. Furthermore, we also evaluated the methodological quality and the quality of prove for all identified associations by using validated tools. By uncovering enquiry gaps, nosotros could identify relevant future enquiry directions.

This umbrella review also had some limitations. Get-go, we did not include qualitative systematic reviews. 2d, misreckoning was the major business in meta-analyses based on observational studies. Although the most of import confounders were adjusted for in most of the chief studies (82% for age and sex, 78% for smoking, seventy% for educational level, and 65% for BMI and total free energy intake), the residual confounders could non be completely avoided. For instance, simply 46% of the studies adjusted for alcohol intake, which should be considered in farther studies. 3rd, some new individual primary studies and primary studies that were not included in any published meta-analyses might accept been missing, besides as some outcomes without meta-analysis were not summarized. Finally, owing to the limited studies, nosotros did non conduct subgroup analysis (e.grand., exploring by historic period, sex, geographical location), or sensitive analysis (e.g., excluding studies with high risks), and other relevant factors might have been missed. For example, regarding dietary zinc intake and the incidence of depression, evidence showed the difference between US, Asian, and European populations, with a decreased incidence of depression in Asian and US populations, and no association for European countries [106].

Conclusions and futurity directions

The present umbrella review provided a comprehensive overview of the currently available meta-analyses focusing on the human relationship betwixt dietary factors and the prevention and treatment of depression. There was moderate-quality bear witness for the inverse associations betwixt adherence to a healthy nutrition, loftier AHEI or AHEI-2010 diet scores, fish, coffee, light to moderate alcohol intake, and dietary zinc intake, and the gamble of low. In addition, several meta-analyses were identified for the positive association between SSBs intake and the risk of depression, assessed as the moderate quality of evidence. Moderate quality of prove had been plant of the therapeutic furnishings of probiotics, n-3 PUFA, and ALC supplementation on depression as well.

To achieve high-quality show for the impact of dietary factors on depression, and be able to describe stiff conclusions, future studies should pay attention to several aspects. It should be foremost to improve dietary measurement tools and get dietary information with high validity in observational studies. Depression cess is another business of the investigation in the preventive effect of dietary factors for low. DSM-Iv applied by experienced psychiatrists should be considered in inquiry equally the "gold standard". Although questionnaires have high validity for low diagnosis, the end-points on the same scale are inconsistent among studies. Farther exploration on standardizing the application of these questionnaires to control heterogeneities is needed. Moreover, studies should investigate exposures that have biological potential effects on depression, only for which no summary evidence is available, or the current quality of evidence is depression. We found no meta-analysis examining the association between intake of whole-grain/cereals, nuts, legumes, dairy products, dietary calcium, or dietary fe and the risk of depression, which could have a potential outcome on depression. More studies are also needed on specific food or nutrients, such equally prebiotics, tea, n-three PUFA, vitamin D, and B vitamins. Considering the methodological quality, authors should be more than careful in the synthesis of master studies, for example, to avoid including dissimilar study designs, pooling unlike exposures or outcomes, and double computing the aforementioned population. Sufficient assessments of the risk of bias of included studies using valid tools are needed for hereafter meta-analyses. If possible, conducting linear or nonlinear dose-response meta-analysis would exist more persuasive. Meanwhile, it is highly recommended for authors to register a protocol (e.g., PROSPERO) prior to conduction, use a satisfactory technique for assessing and accounting bias, and follow standardized guidelines such as the PRISMA, to ensure high methodological quality.

References

-

Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with inability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Written report 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

-

Sinyor K, Rezmovitz J, Zaretsky A. Screen all for depression. BMJ. 2016;352:i1617 https://doi.org/ten.1136/bmj.i1617

-

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola Due south, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for feet, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:841–50. https://doi.org/ten.1016/s0140-6736(07)61414-7

-

Orsolini L, Latini R, Pompili M, Serafini G, Volpe U, Vellante F, et al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: from research to clinics. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17:207–21. https://doi.org/ten.30773/pi.2019.0171

-

WHO. Depression. 2018. http://world wide web.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/depression.

-

Lohoff FW. Overview of the genetics of major depressive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:539–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-010-0150-6

-

Dana-Alamdari L, Kheirouri Due south, Noorazar SG. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in patients with major depressive disorder. Islamic republic of iran J Public Health. 2015;44:690–vii.

-

Mammen G, Faulkner Thousand. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:649–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001

-

Pudrovska T, Karraker A. Gender, job say-so, and depression. J Wellness Soc Behav. 2014;55:424–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146514555223

-

Simon S, Cain NM, Wallner Samstag L, Meehan KB, Muran JC. Assessing interpersonal subtypes in low. J Pers Assess. 2015;97:364–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1011330

-

Arias-de la Torre J, Puigdomenech E, García X, Valderas JM, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Fernández-Villa T, et al. Relationship between low and the use of mobile technologies and social media amid adolescents: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e16388 https://doi.org/ten.2196/16388

-

Opie RS, Itsiopoulos C, Parletta Due north, Sanchez-Villegas A, Akbaraly TN, Ruusunen A, et al. Dietary recommendations for the prevention of depression. Nutr Neurosci. 2017;20:161–71. https://doi.org/10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000043

-

Popa TA, Ladea M. Nutrition and low at the forefront of progress. J Med Life. 2012;5:414–9.

-

Köhler CA, Evangelou E, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N, Belbasis L, et al. Mapping risk factors for low beyond the lifespan: an umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and Mendelian randomization studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:189–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.020

-

Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, Jacka F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Kivimäki M, et al. Salubrious dietary indices and chance of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:965–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0237-viii

-

Sanhueza C, Ryan 50, Foxcroft DR. Diet and the gamble of unipolar depression in adults: systematic review of accomplice studies. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26:56–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01283.ten

-

Dinu Yard, Pagliai 1000, Casini A, Sofi F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:30–43. https://doi.org/x.1038/ejcn.2017.58

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grouping P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535 https://doi.org/ten.1136/bmj.b2535

-

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

-

Schwingshackl 50, Knüppel S, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann Thou, Missbach B, Stelmach-Mardas 1000, et al. Perspective: NutriGrade: a scoring system to assess and approximate the meta-show of randomized controlled trials and accomplice studies in nutrition research. Adv Nutr. 2016;vii:994–1004. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.013052

-

Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, Jacka F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Kivimäki M, et al. Good for you dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-assay of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:965–86. https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41380-018-0237-8

-

Askari, M, Daneshzad E, Mofrad Doc, Bellissimo N, Suitor Thou, Azadbakht L. Vegetarian nutrition and the risk of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Nutrient Sci Nutr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1814991.

-

Tolkien Chiliad, Bradburn S, Murgatroyd C. An anti-inflammatory nutrition equally a potential intervention for depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:2045–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.007

-

Shafiei F, Salari-Moghaddam A, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and run a risk of depression: a systematic review and updated meta-assay of observational studies. Nutr Rev. 2019;77:230–nine. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuy070

-

Firth J, Marx W, Nuance S, Carney R, Teasdale SB, Solmi M, et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of low and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2019;81:265–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000673

-

Molendijk 1000, Molero P, Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño F, Van der Does W, Angel Martínez-González M. Nutrition quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:346–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022

-

Li Y, Lv MR, Wei YJ, Sun L, Zhang JX, Zhang HG, et al. Dietary patterns and depression chance: a meta-assay. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:373–82. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.020

-

Ein Northward, Armstrong B, Vickers K. The event of a very low calorie diet on subjective depressive symptoms and feet: meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Obes. 2019;43:1444–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0245-4

-

Pagliai G, Dinu Grand, Madarena MP, Bonaccio Yard, Iacoviello L, Sofi F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2021;125:308–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114520002688.

-

Fusar-Poli L, Gabbiadini A, Ciancio A, Vozza L, Signorelli MS, Aguglia E. The consequence of cocoa-rich products on depression, anxiety, and mood: a systematic review and meta-assay. Crit Rev Nutrient Sci Nutr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1920570.

-

Nucci D, Fatigoni C, Amerio A, Odone A, Gianfredi V. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186686.

-

Li J, Wang H, Li M, Shen Q, Li X, Zhang Y, et al. Event of alcohol use disorders and alcohol intake on the gamble of subsequent depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2020;115:1224–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/add together.14935

-

Hu D, Cheng L, Jiang Westward. Sugar-sweetened beverages consumption and the risk of low: a meta-assay of observational studies. J Touch on Disord. 2019;245:348–55. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jad.2018.11.015

-

Yang Y, Kim Y, Je Y. Fish consumption and risk of depression: epidemiological evidence from prospective studies. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;x:e12335 https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12335

-

Saghafian F, Malmir H, Saneei P, Milajerdi A, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of depression: accumulative evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. 2018;119:1087–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114518000697

-

Grosso G, Micek A, Castellano S, Pajak A, Galvano F. Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Nutr Nutrient Res. 2016;threescore:223–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201500620

-

Kang D, Kim Y, Je Y. Not-alcoholic potable consumption and take a chance of depression: epidemiological evidence from observational studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:1506–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0121-2

-

Wang Fifty, Shen 10, Wu Y, Zhang D. Coffee and caffeine consumption and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Aust Northward Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:228–42. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0004867415603131

-

Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for low and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;102:thirteen–23. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.023

-

Yosaee S, Clark C, Keshtkaran Z, Ashourpour One thousand, Keshani P, Soltani S. Zinc in depression: from development to treatment: a comparative/ dose response meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.08.001

-

Li B, Lv J, Wang Due west, Zhang D. Dietary magnesium and calcium intake and run a risk of depression in the general population: a meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:219–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867416676895

-

Deane KHO, Jimoh OF, Biswas P, O'Brien A, Hanson S, Abdelhamid AS, et al. Omega-3 and polyunsaturated fat for prevention of depression and feet symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.234.

-

Grosso Thousand, Micek A, Marventano S, Castellano Due south, Mistretta A, Pajak A, et al. Dietary north-3 PUFA, fish consumption and low: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Impact Disord. 2016;205:269–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.011

-

Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, He Q, Guo Fifty, Subramaniapillai M, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in low: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:190 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0515-5

-

Veronese North, Stubbs B, Solmi Yard, Ajnakina O, Carvalho AF, Maggi Southward. Acetyl-l-carnitine supplementation and the treatment of depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-assay. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:154–9. https://doi.org/x.1097/psy.0000000000000537

-

Lázaro Tomé A, Reig Cebriá MJ, González-Teruel A, Carbonell-Asíns JA, Cañete Nicolás C, Hernández-Viadel M. Efficacy of vitamin D in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2021;49:12–23.

-

Sarris J, Tater J, Mischoulon D, Papakostas GI, Fava M, Berk Thousand, et al. Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:575–87. https://doi.org/ten.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15091228

-

Young LM, Pipingas A, White DJ, Gauci S, Scholey A. A systematic review and meta-assay of B vitamin supplementation on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress: effects on salubrious and 'at-risk' individuals. Nutrients. 11, 2019. https://doi.org/ten.3390/nu11092232.

-

Montagnese C, Santarpia Fifty, Buonifacio M, Nardelli A, Caldara AR, Silvestri Due east, et al. European food-based dietary guidelines: a comparison and update. Nutrition. 2015;31:908–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.01.002

-

Montagnese C, Santarpia 50, Iavarone F, Strangio F, Sangiovanni B, Buonifacio M, et al. Food-based dietary guidelines around the globe: Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries. Nutrients 11, 2019. https://doi.org/ten.3390/nu11061325.

-

Ventriglio A, Sancassiani F, Contu MP, Latorre 1000, Di Slavatore Thou, Fornaro M, et al. Mediterranean nutrition and its benefits on wellness and mental health: a literature review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2020;xvi:156–64.

-

Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Gea A, Ruiz-Canela K. The Mediterranean nutrition and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2019;124:779–98. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313348

-

Berk Chiliad, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O'Neil A, Pasco JA, Moylan S, et al. So depression is an inflammatory affliction, but where does the inflammation come up from? BMC Med. 2013;xi:200 https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-200

-

Moylan S, Berk M, Dean OM, Samuni Y, Williams LJ, O'Neil A, et al. Oxidative & nitrosative stress in low: why and so much stress? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:46–62. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.05.007

-

Fernandes BS, Steiner J, Molendijk ML, Dodd Due south, Nardin P, Gonçalves CA, et al. C-reactive protein concentrations beyond the mood spectrum in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-assay. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:1147–56. https://doi.org/ten.1016/S2215-0366(xvi)30370-4

-

Harasym J, Oledzki R. Issue of fruit and vegetable antioxidants on total antioxidant capacity of blood plasma. Nutrition. 2014;thirty:511–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.019

-

Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki Grand, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in heart age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:408–13. https://doi.org/ten.1192/bjp.bp.108.058925

-

Polokowski AR, Shakil H, Carmichael CL, Reigada LC. Omega-3 fatty acids and anxiety: a systematic review of the possible mechanisms at play. Nutr Neurosci. 2020;23:494–504. https://doi.org/x.1080/1028415x.2018.1525092

-

Chang CY, Ke DS, Chen JY. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2009;18:231–41.

-

Appleton KM, Sallis HM, Perry R, Ness AR, Churchill R. Omega-three fatty acids for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD004692, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004692.pub4.

-

Hibbeln JR, Linnoila M, Umhau JC, Rawlings R, George DT, Salem Northward Jr. Essential fat acids predict metabolites of serotonin and dopamine in cerebrospinal fluid among salubrious control subjects, and early- and late-onset alcoholics. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:235–42. https://doi.org/ten.1016/s0006-3223(98)00141-3

-

Sanchez-Villegas A, Zazpe I, Santiago South, Perez-Cornago A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Lahortiga-Ramos F. Added sugars and sugar-sweetened drinkable consumption, dietary carbohydrate index and depression run a risk in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project. Br J Nutr. 2018;119:211–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114517003361

-

Knuppel A, Shipley MJ, Llewellyn CH, Brunner EJ. Sugar intake from sweetness nutrient and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall Ii written report. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6287 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05649-seven

-

McInnis CM, Thoma MV, Gianferante D, Hanlin Fifty, Chen X, Breines JG, et al. Measures of adiposity predict interleukin-half dozen responses to repeated psychosocial stress. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2014;42:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.018

-

Harrell CS, Burgado J, Kelly SD, Johnson ZP, Neigh GN. High-fructose diet during periadolescent evolution increases depressive-like beliefs and remodels the hypothalamic transcriptome in male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:252–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.025

-

Wang J, Light K, Henderson M, O'Loughlin J, Mathieu ME, Paradis One thousand, et al. Consumption of added sugars from liquid but not solid sources predicts impaired glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance among youth at risk of obesity. J Nutr. 2013;144:81–86. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.182519

-

Mannan M, Mamun A, Doi South, Clavarino A. Prospective associations betwixt depression and obesity for adolescent males and females—a systematic review and meta-assay of longitudinal studies. PLoS Ane. 2016;11:e0157240 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157240

-

Bruce DG, Davis WA, Starkstein SE, Davis TME. Clinical risk factors for depressive syndrome in type 2 diabetes: the fremantle diabetes report. Diabet Med. 2018;35:903–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13631

-

Teesson M, Hall W, Slade T, Mills K, Grove R, Mewton L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in Australia: findings of the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Habit. 2010;105:2085–94. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03096.ten

-

Chou SP, Lee HK, Cho MJ, Park JI, Dawson DA, Grant BF. Alcohol utilize disorders, nicotine dependence, and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders in the Usa and Republic of korea-a cantankerous-national comparison. Booze Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:654–62. https://doi.org/ten.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01639.x

-

Sanchez-Roige S, Palmer AA, Fontanillas P, Elson SL, Research Team, the Substance Employ Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C, Adams MJ, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Meta-Analysis of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in two population-based cohorts. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:107–18. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18040369

-

Zhao LG, Li ZY, Feng GS, Ji XW, Tan YT, Li HL, et al. Coffee drinking and cancer risk: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:101 https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12885-020-6561-9

-

Kim TL, Jeong GH, Yang JW, Lee KH, Kronbichler A, van der Vliet HJ, et al. Tea consumption and take a chance of cancer: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Adv Nutr. 2020;eleven:1437–52. https://doi.org/ten.1093/advances/nmaa077

-

Yi K, Wu 10, Zhuang Westward, Xia Fifty, Chen Y, Zhao R, et al. Tea consumption and health outcomes: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies in humans. Mol Nutr food Res. 2019;63:e1900389 https://doi.org/ten.1002/mnfr.201900389

-

Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J. Coffee consumption and wellness: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple wellness outcomes. BMJ. 2017;359:j5024 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5024

-

Grosso 1000, Godos J, Galvano F, Giovannucci Due east. Coffee, caffeine, and health outcomes: an umbrella review. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017;37:131–56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064941

-

Godos J, Pluchinotta FR, Marventano S, Buscemi S, Li Volti Yard, Galvano F, et al. Coffee components and cardiovascular hazard: beneficial and detrimental effects. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014;65:925–36. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2014.940287

-

Walker J, Rohm B, Lang R, Pariza MW, Hofmann T, Somoza V. Identification of coffee components that stimulate dopamine release from pheochromocytoma cells (PC-12). Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;l:390–8. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.fct.2011.09.041

-

Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, Anderson IM, Christmas D, Cowen PJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:459–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115581093

-

Bauer M, Pfennig A, Severus E, Whybrow PC, Malaise J, Möller HJ, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, office one: update 2013 on the astute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14:334–85. https://doi.org/ten.3109/15622975.2013.804195

-

Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of handling-resistant low. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:649–59. https://doi.org/x.1016/s0006-3223(03)00231-two

-

Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;nine:41–46.

-

Goethe JW, Woolley SB, Cardoni AA, Woznicki BA, Piez DA. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: side effects and other factors that influence medication adherence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:451–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815152a5

-

Marx Due west, Moseley Yard, Berk G, Jacka F. Nutritional psychiatry: the present country of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:427–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665117002026

-

Chen CT, Domenichiello AF, Trépanier MO, Liu Z, Masoodi K, Bazinet RP. The low levels of eicosapentaenoic acid in rat encephalon phospholipids are maintained via multiple redundant mechanisms. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2410–22. https://doi.org/ten.1194/jlr.M038505

-

Mischoulon D, Best-Popescu C, Laposata M, Merens W, Murakami JL, Wu SL, et al. A double-blind dose-finding pilot study of docosahexaenoic acrid (DHA) for major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:639–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.04.011

-

Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Yassini-Ardakani M, Karamati M, Shariati-Bafghi SE. Eicosapentaenoic acid versus docosahexaenoic acid in mild-to-moderate depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:636–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.08.003

-

Luo XD, Feng JS, Yang Z, Huang QT, Lin JD, Yang B, et al. High-dose omega-3 polyunsaturated fat acid supplementation might exist more than superior than low-dose for major depressive disorder in early therapy period: a network meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:248 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02656-iii

-

Yang B, Lin L, Bazinet RP, Chien YC, Chang JP, Satyanarayanan SK, et al. Clinical efficacy and biological regulations of omega-3 PUFA-derived endocannabinoids in major depressive disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88:215–24. https://doi.org/ten.1159/000501158

-

Song C, Shieh CH, Wu YS, Kalueff A, Gaikwad S, Su KP. The role of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in the treatment of major low and Alzheimer's disease: interim separately or synergistically? Prog Lipid Res. 2016;62:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2015.12.003

-

Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ. Meta-analysis of the furnishings of eicosapentaenoic acrid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1577–84. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06634

-

Hallahan B, Ryan T, Hibbeln JR, Murray IT, Glynn S, Ramsden CE, et al. Efficacy of omega-iii highly unsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of low. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:192–201. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160242

-

Gold Pow, Licinio J, Pavlatou MG. Pathological parainflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in depression: potential translational targets through the CNS insulin, klotho and PPAR-γ systems. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:154–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.167

-

Mochizuki K, Suruga Thousand, Fukami H, Kiso Y, Takase S, Goda T. Selectivity of fatty acid ligands for PPARalpha which correlates both with binding to cis-element and DNA binding-independent transactivity in Caco-two cells. Life Sci. 2006;80:140–5. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.029

-

Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota limerick in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;48:186–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016

-

Naseribafrouei A, Hestad G, Avershina E, Sekelja 1000, Linløkken A, Wilson R, et al. Correlation between the human being fecal microbiota and depression. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1155–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12378

-

Marcos A, Wärnberg J, Nova East, Gómez S, Alvarez A, Alvarez R, et al. The effect of milk fermented by yogurt cultures plus Lactobacillus casei DN-114001 on the immune response of subjects under academic examination stress. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43:381–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-004-0517-eight

-

Wallace CJK, Milev R. The furnishings of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-017-0138-2

-

Ng Q, Peters C, Ho C, Lim D, Yeo W. A meta-analysis of the use of probiotics to alleviate depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2018;228:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.063

-

Jones LL, McDonald DA, Borum PR. Acylcarnitines: part in brain. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:61–75. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.plipres.2009.08.004

-

Pettegrew JW, Levine J, Gershon S, Stanley JA, Servan-Schreiber D, Panchalingam One thousand, et al. 31P-MRS study of acetyl-l-carnitine treatment in geriatric depression: preliminary results. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:61–66. https://doi.org/ten.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01180.ten

-

Pettegrew JW, Levine J, McClure RJ. Acetyl-50-carnitine concrete-chemic, metabolic, and therapeutic properties: relevance for its fashion of activity in Alzheimer's affliction and geriatric depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:616–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4000805

-

Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU. A review of current evidence for acetyl-l-carnitine in the handling of low. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:thirty–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.02.005

-

Młyniec M, Davies CL, Budziszewska B, Opoka Due west, Reczyński W, Sowa-Kućma G, et al. Time grade of zinc impecuniousness-induced alterations of mice behavior in the forced swim examination. Pharm Rep. 2012;64:567–75. https://doi.org/ten.1016/s1734-1140(12)70852-6

-

Mlyniec Chiliad, Nowak G. Zinc deficiency induces behavioral alterations in the tail suspension test in mice. Effect of antidepressants. Pharm Rep. 2012;64:249–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70762-iv

-

Li Z, Li B, Vocal 10, Zhang D. Dietary zinc and atomic number 26 intake and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.006

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

YJX, LNZ, GC, and LLZ designed the study. YJX, LNZ, KZ, SFS, and XYW screened, extracted, and evaluated the evidence. YJX, LNZ, and JYX conducted the analysis of the information. YJX drafted the manuscript under the guidance and supervision of GC and LLZ. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ideals declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's notation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and bespeak if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this commodity are included in the article's Artistic Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If cloth is not included in the article'south Creative Eatables license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Zeng, Fifty., Zou, Grand. et al. Function of dietary factors in the prevention and handling for low: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective studies. Transl Psychiatry 11, 478 (2021). https://doi.org/x.1038/s41398-021-01590-6

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01590-6

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-021-01590-6